Understanding Grief: Navigating Loss and Prolonged Grief Disorder

February 27, 2024 Posted by AHW Endowment

Grief is a universal human response to loss, particularly the loss of someone or something we deeply care about. It is a deeply personal experience that can vary greatly from person to person and is a necessary part of healing and adapting to life after loss. While experiencing a loss can be challenging, most people return to their daily lives within a year. For some individuals, experiencing a loss can lead to complications with grief that cause clinically diagnosable mental health issues such as depression and prolonged grief disorder (PGD).

In a recent episode of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment’s (AHW’s) monthly livestream, Coffee Conversations with Scientists, Joseph Goveas, MD, professor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, and Institute for Health and Equity and vice-chair and director, Geriatric Psychiatry at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), shared his expertise and experience in a discussion about the risks, symptoms, and interventions for prolonged grief.

In a recent episode of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment’s (AHW’s) monthly livestream, Coffee Conversations with Scientists, Joseph Goveas, MD, professor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, and Institute for Health and Equity and vice-chair and director, Geriatric Psychiatry at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), shared his expertise and experience in a discussion about the risks, symptoms, and interventions for prolonged grief.

Understanding Grief After a Loss

It’s natural for people to grieve after a loss, and for six to 12 months after that happens, it can be expected. In that time, many adapt and can find purpose, re-engage in their daily lives, and regulate the feelings and emotions around their loss experience.

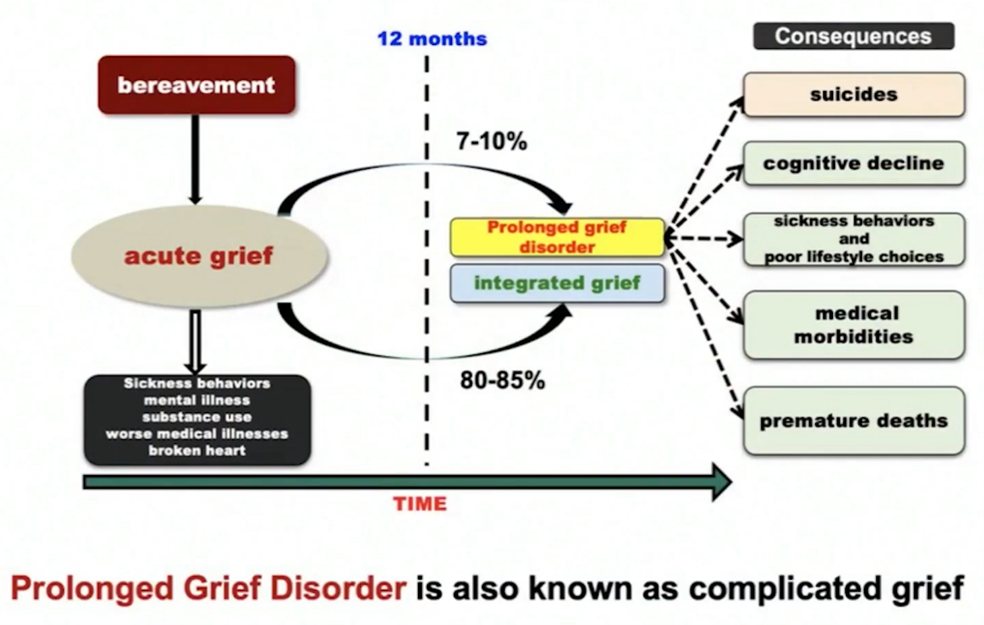

However, 7-10% of individuals who lose an attachment figure in their lives see their grief become prolonged and pervasive, interfering with their ability to function and developing symptoms that can last for years. PGD is the result of feelings and behaviors originating in the brain, and for Dr. Goveas and his peers, studying how the brain works and functions while navigating grief is the focal point for research on how grief affects both mental and physical health.

According to Dr. Goveas, there are two types of grief that manifest clinically: acute and prolonged. Acute grief can be experienced by anyone who deals with a loss, within the first year of it happening. While symptoms of acute grief vary from person to person, yearning or longing for a lost person or thing, intense emotional pain, sadness, bitterness, and anger are common. Interference in appetite or sleep patterns might even be expected for the first few months after a loss, all of which are normal as individuals balance their grief while needing to function in their lives. Over time, grief symptoms decrease as a person transitions to integrated grief, or the grief that remains after we’ve dealt with a loss and accepted its meaning.

(Chart provided by Dr. Goveas)

When Acute Grief Becomes Prolonged Grief Disorder

When severe grief symptoms persist for more than one year, they can develop into PGD, which may lead to cognitive decline and other illnesses with the potential for premature death. “There are indications that in those with prolonged grief, they experience poorer attention span and concentration, but more importantly, difficulties in decision-making and memory difficulties. Some early results show that in some individuals with PGD, there is an association with future cognitive decline, especially in their memory performance over time,” said Dr. Goveas.

He went on to explain that in one of his research studies, older adults who experience intense grief symptoms with cognitive effects such as decision-making, attention, and processing speed, see an acceleration in the development of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

As Dr. Goveas and his peers explore the long-term effects of prolonged grief, they have seen early indications that it can result in an overall decrease in brain volume compared to individuals who are not grieving. There are also studies examining cognition and memory that have indicated older adults who lose their life partner experience a cognitive decline that is three-times the rate of cognitive decline in married older adults, making them more susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers at MCW use functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologies that allow them to view two circuit areas of the brain that deal with emotional regulation and rewarding processing. As loss triggers an emotional experience that leads to dysregulated emotions, new research funded by the AHW will explore the hypothesis that aberration in brain circuitries that underly emotional dysregulation will be seen in prolonged grief. Early findings support the idea that there is increased activity in the amygdala brain region involved with sadness and storing emotional memory, which seems to be hyperactive in people with PGD and might explain some key grief symptoms.

Additionally, Dr. Goveas and peers are exploring the widely accepted Theory of Attachment (the close bonds that we form with attachment figures) and the way the brain’s reward circuitry reacts to losing an attachment figure.

Bereavement and Other Consequences of Grief

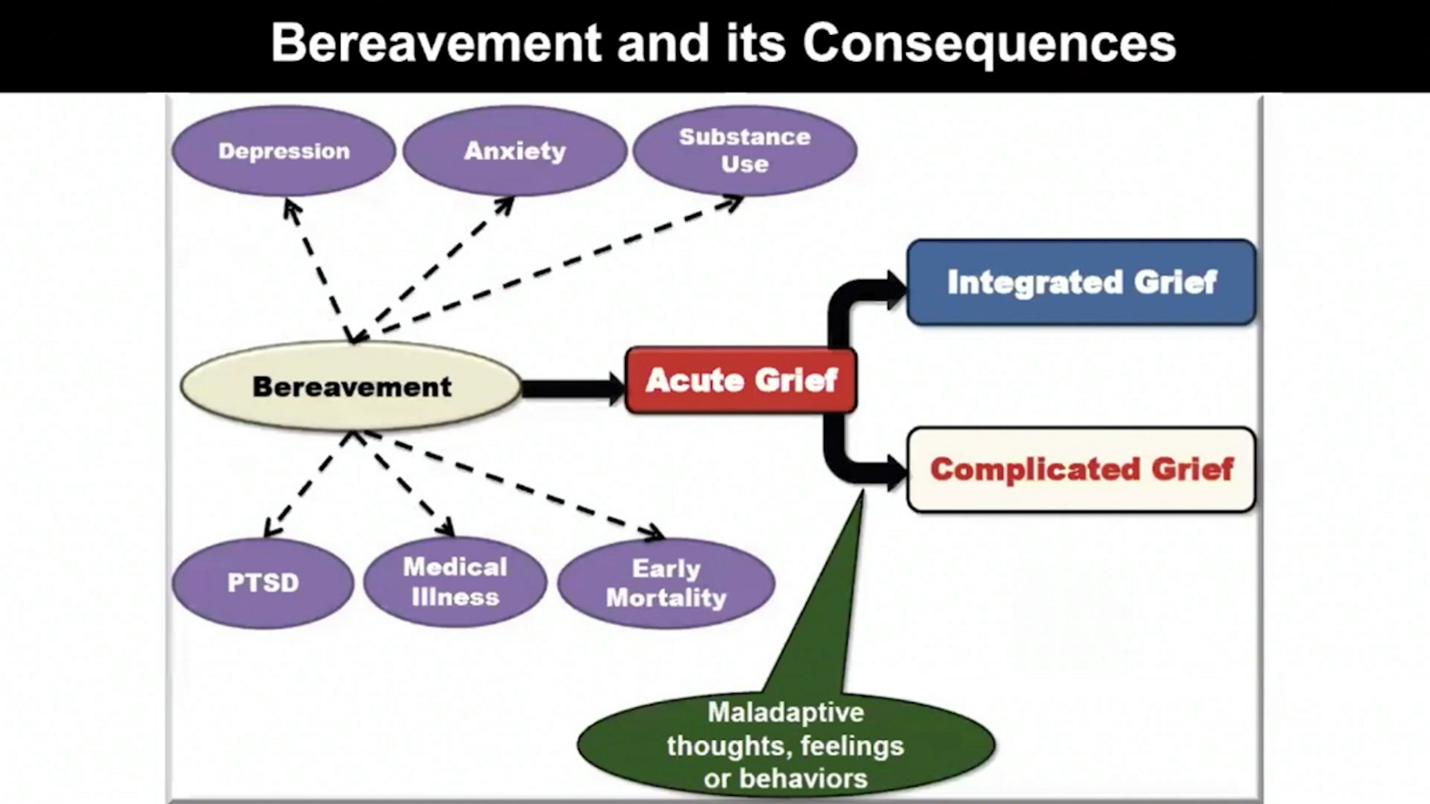

Beyond grief, bereavement (the process of mourning a loss) can lead to consequences including depression, anxiety, substance use, PTSD, and illnesses. At MCW, Dr. Goveas and other researchers are examining how identifying bereavement factors early on might improve long-term health outcomes for those who suffer a loss.

The Developing Resilience to Ease Anguish in Morning (DREAM) program at MCW, “… examines factors that can complicate acute grief following the loss of a loved one, to identify interventions that prevent grief-related complications.” The program also aims to identify treatments that can improve long-term health outcomes in those experiencing prolonged grief disorder and bereavement-related depression.

(Chart provided by Dr. Goveas)

Navigating Grief After a Loss

It’s inevitable that, as we age, we will all experience more losses. Each loss is and will be unique, and each person grieves differently. There are certain actions we can take, however, as we go through the grieving process to create the best outcomes for ourselves.

Dr. Goveas mentioned that focusing on self-care and being compassionate toward ourselves, and those around us who are grieving, is important. Facilitating healing and getting involved in activities and experiences that brought us joy previously can help prevent grief from overwhelming our thoughts and feelings.

Connecting with others and creating opportunities to welcome their support, and in turn, provide support and a listening ear to others experiencing grief, can be important steps in staying engaged and active in processing grief and moving forward in adapting to a loss.

There are resources available to individuals experiencing grief and seeking help navigating their feelings, such as the Southeast Grief Network, which provides support with events, resources, training opportunities, and knowledge. The Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin Grief Clinic also offers services to support the acute grieving process as well as complicated grief, PGD, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.

Learn More About Grief

Want to hear more from Dr. Goveas about grief and prolonged grief disorder? Watch the full episode of Coffee Conversations with Scientists here:

.png?width=300&name=Funding%20Announcement%20(2).png)